An email this morning got me thinking.

Dear Ken

I’m not sure you’d remember me, but I used to go to Hereford Sixth Form College and sang in the choir and you did several events and workshops with us whilst I was there. I’m now an undergraduate at Merton College, Oxford and am writing an extended essay as part of my First Year syllabus entitled ‘Appropriation and Erasure of the ‘Spiritual’ in Michael Tippett’s ‘A Child of our Time’. I noticed that on April 14th the ESO is putting on a concert which includes excerpts from ‘A Child of Our Time’, listed as ‘Five Negro Spirituals’. As Artistic Director, I wondered if I might ask how you would respond to a view that the use of the word ‘Negro’ in the programme is outdated and ignorant to modern perceptions and the inherently racial history of the word? I know it’s used the original score and Tippett’s own description of his work, but is omitted from modern publications and is arguably unnecessary to the description of the musical material.

A.S.

Dear A.S.

Thanks for writing.

My first response to your message was simply that I’m not conducting this concert and so hadn’t been involved in the marketing. However, it’s perfectly reasonable, as you suggest, that the Artistic Director should have a view. And so, I shall attempt an answer. Since this is a big topic, I hope you won’t mind me re-using this as a blog post.

As I am sure you are well aware, this is a very timely and fraught issue, and potentially touches on a number of sensitive issues that are being hotly debated. It goes beyond the question of whether the word ‘Negro’ should still be used, and extends to questions of cultural ownership and appropriation (a word I see you’ve used in the title of your essay) and questions of the rightful ownership of art and history. I would be very interested to read your essay – it’s a pretty provocative title.

So fraught are some of these questions today in academia (and elsewhere) that I did think carefully before putting my thoughts on the matter in writing. I have seen attempts at constructive discussion of these issues turn very ugly. Encouraged by your former mentors at HSFC, I have decided to attempt to articulate my views.

Let’s for the moment divide the questions around this work into two areas- the first being the issue of ‘appropriation’ and the second being the use of words like ‘Negro.’

Appropriation doesn’t exist?

I personally believe that music and art cannot be appropriated by musicians and artists. Anyone that wants to play, study or engage with any piece of music has an equal and total right to do so. Music is there for musicians and people, and it belongs to us all equally and completely. It can certainly be exploited and degraded by commercialism and politics, and this is an area of musicology which ought to be more carefully studied. Whether it is using the slow movement of Dvorak’s 9th Symphony as the soundtrack for a bread commercial or playing Liszt’s Les Preludes at Nazi rallies, I find this kind of use of music (one might call it ‘manipulative exploitation’) to be troubling, regardless of the genre of music.

However, Tippett’s use of spirituals seems to me to be very much part of the long tradition of quotation and reference that is part of what makes music such a rich and interesting art-form. While the most obvious comparison to the Tippett is Bach’s inclusion of Lutheran chorales in his Passions, references to vernacular and sacred music are an important part of art music of all kinds. Mahler’s music literally overflows with references, quotations and pastiches of other genres and musics, from Klezmer and Bohemian band music to operetta and waltzes. Mahler’s use of vernacular music was, and remains, controversial and was often part of the criticism levied against him in the anti-Semitic part of the Viennese press in his lifetime. A common argument was that the “Jewish Mahler” was cheapening the “German Symphony” by his inclusion of non-German musics like Klezmer, in doing so, desecrating the genre perfected by Beethoven. These critics forget that Beethoven’s symphonies are full of quotes and references to Turkish marches and French Revolutionary songs, bits of Bach Passions. and quotes from Mozart. To these same critics, if Mahler quoted from Bach, he was desecrating or ‘appropriating’ Bach by putting it alongside kitsch..

Shostakovich is a composer whose output cries out for a major English-language study of his use of quotation, which is far more varied and extensive than almost any Western listener realises. His music quotes obsessively from the great works of the Western canon (Bach, Beethoven, Wagner, Mahler and Bruckner) alongside jazz, Orthodox chant, Russian and Eastern European folk music and more. The Russian folk, religious and popular references in particular are so pervasive and wide-ranging that’s not hard to make the case that Western listeners can’t hope to comprehend a huge proportion of what his music says, as popular as it is. Does this mean we shouldn’t play his music?

The argument I hear most often against the sort of thing Tippett has done in A Child of Our Time is that borrowing the music of another culture for a new piece is no different, and is possibly worse than the examples of Liszt and Dvorak I gave above being used in ‘manipulative exploitation.’ Many contend this is the exploitation of the cultural legacy of a disadvantaged group of people by the dominant culture. I’ve heard it described as the perpetuation of the legacy of colonialism or slavery.

While I understand that argument, I strongly disagree with it.

Music belongs to everyone

First, I don’t believe any person has a right to tell another person they can’t, or shouldn’t, engage with, perform, study, quote or re-compose another piece of music. The arguments I hear against what Tippett has done are essentially the same ones one can see used against jazz musicians of the mid 20th Century referencing the music of Ravel, Bartók and Stravinsky in their music. There is a long, dark history of racism in classical music that says Asian (particularly Japanese, Chinese and Korean) musicians are “too obsessed with technical perfection and don’t play with emotion” or that black musicians don’t understand classical music’s European roots. It was once assumed that women musicians couldn’t play ‘big’ works with the same power and intensity as men. You are surely aware of the long history of racist comments about Jewish musicians, including figures as important as Mendelssohn and Mahler. Wagner was by no means the only major musician to put his racist beliefs about Jewish artists’ musical performance into the historical record. I don’t think any reasonable person can argue that the Jews have ever been a dominant culture in Europe. Saying a white musician can’t do justice to or should play jazz or spirituals automatically gives a perfect argument to those who would keep people of non-European descent, and women, from playing classical music. Music belongs to whoever loves it, treats it with respect and does it justice. Any musical person can learn, and do justice to, the musical language of another culture, just as belonging to a given culture doesn’t in anyway mean you understand or can replicate the music of that culture. Most white Europeans know next to nothing about Beethoven and Wagner and couldn’t play a note of it if they tried, while there are fantastic orchestras of people of all colours and backgrounds all over the world who play European music with consummate skill and understanding. This is not to say that there aren’t plenty of examples of people desecrating and degrading the music of other cultures. I often feel very uncomfortable listening to all-white choirs in all-white churches in all-white suburbs in America singing ‘African’ music. Engaging with the music of another culture means really engaging, and most times I see these kind of performances I just find it totally wrong musically and culturally. A lazy or superficial or insincere engagement with any music, from any culture, will always yield a cringe-worthy result. When it is music from a culture you don’t understand, the result is likely to be doubly awful

My own love of jazz and blues music and my desire to transcend the whiteness of my own guitar playing taught me a lot. I can remember being in a jam session in my late teens and suddenly, painfully realising how incredibly inauthentic and white I sounded. My response was not to leave jazz and blues to black musicians, but to really study the music and the culture it came from much, much more deeply. I learned an enormous amount about all music as a result. I passionately believe that anyone who loves music should be able to study it and try to do it justice, no matter who they are or what they look like. Miles Davis said that, as a rule, “white guys can’t play jazz,” but then went on immediately to point out that Gill Evans and Bill Evans (both white, no relation) were two of his most important collaborators. Most white guys can’t play jazz because most white guys don’t try hard enough. But most white guys can’t play Mozart, either.

It’s not what you borrow, it’s what you borrow it for

And that brings me to my second point. A Child of Our Time is a great work of art by a musician of great seriousness of both artistic and moral purpose. Assessing whether or not Tippett’s approach is “right” requires us to engage directly with the quality and importance of what he has done. Does he do justice to his materials, to his subject matter and to his aims in this piece? Surely he does.

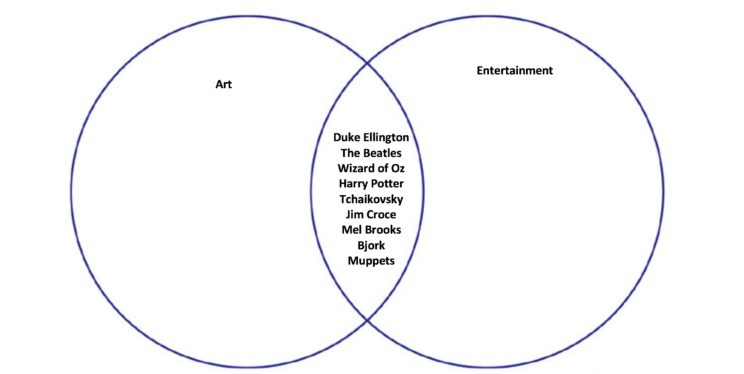

True musical and cultural criticism is something of a dying art these days. Instead, we live in a cultural of equivalence. A generation ago, art and entertainment were accepted as being very different things. Both had merit, but it was generally uncontroversial that art had greater value than entertainment.

This has had the lamentable side effect that many works of art that emerged from within the entertainment industry took a long time to be taken seriously on their artistic merits. Also, art that emerged through unconventional genres, cultures or traditions was often overlooked. Whether it was the Beatles, Robert Johnson or Henry Darger, it has taken time for much music, literature and visual art from outside the mainstream artistic traditions to be assessed with the seriousness it deserved. On the other hand, there are fundamental differences between art, entertainment, marketing and politicking, and within each of those areas there are huge varieties of quality and what, for lack of a better word, I will call ‘justifyability.’

Art’s intrinsic value

I would contend that the justifyability of Tippett’s approach is in the quality and importance of the art that came out of it. To those who ask “who gets to decide what is or isn’t artistically worthwhile?” I would say that nobody gets to decide. The value of a work of art, both aesthetic and moral, is intrinsic. It’s either worthwhile or it isn’t. Tippett’s music is worthwhile not because I say it is, but because it is. Criticism, at its best, is the art of recognition, not of definition. Once created, art may come in and out of fashion. People may try to ban it or burn it. People may denounce it or extol it. They may completely forget it. But the actual value, quality and importance of the work of art itself cannot be changed. Whether any one listener or commentator recognises the value of work of a work of art or understands a work of art it is a question of the perceptive abilities and prejudices of that audience member. But this doesn’t mean that the value of art is all subjective and a matter of opinion. Absolutely the opposite. The value of a single work of art is just as specific and unchanging as the number of grains of sand on a given beech at a given moment, and perhaps just as hard to measure with certainty.

Duke Ellington said it well – “There are two kinds of music. Good music and the other kind.” Ellington’s arrangement of The Nutcracker offended many purists when it came out, and I am sure it would still raise hackles in the right wing of Russian society. Tchaikovsky’s original Nutcracker has endlessly been exploited in advertisements -such use is rarely considered controversial, but I would argue that using Tchaikovsky’s music to sell aftershave is far more questionable than Tippett’s use of spirituals in an important piece of music. Ellington and Billy Strayhorn’s Nutcracker is a wonderful and important work of re-composition, and I am grateful that they did it. To those who would say it is a different thing when a black composer re-uses European music than when a white European composer, as part of a dominant and historically oppressive culture, exploits black music, I would say a few things. First, Tchaikovsky was, as you know, a minority figure- he was gay in a religious and patriarchal society. Second, what do we make of Tchaikovsky’s original? Most composers were or are outsiders in their own cultures (do you know Mahler’s quote “I am thrice homeless, as a native of Bohemia in Austria, as an Austrian among Germans, and as a Jew throughout the world. Everywhere an intruder, never welcomed”) Finally, how does one even define where one musical tradition ends and another begins. Nobody questions whether it is okay for Tchaikovsky to write a Russian dance, but what about the Arab Dance or the Chinese Dance? And when Ellington and Strayhorn re-work them, would they have been appropriating Tchaikovsky, or Arab and Chinese music?

To come back to Tippett, as you are aware, he was hardly part of the oppressive power structures of Western society. Rather the opposite. He was a pacifist who did prison time for his opposition to military service and, as a gay man, his very existence was illegal in the country of his birth until 1967. If ever any white artist had the moral right to use spirituals in his music, it was Tippett.

Should we erase certain words from history?

Finally, let me come back to the use of the word ‘Negro.’

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s6RU8z1HErE

It’s not a word one hears much today, but I have vivid memories of its use in my childhood, both among elders of both races and in movies and on TV. I tend to associate it most powerfully with Martin Luther King and the American Civil Rights movement. For me, it is a word of a bygone time. With that in mind, I think removing the word from the Tippett’s piece eliminates an element of historical placement from Tippett’s work. Yes, one could call them simply “Spirituals” but that runs the risk that their proper attribution becomes lost. Please see my essay on Dvorak’s American Quartet for an example of how the roots of music used in a very famous piece can be completely forgotten in a couple of generations. The Dvorak poses a special challenge because its original nickname is truly unacceptable in modern discourse and needed to change, but I think it’s important that the memory of the original title not be lost.

One could now call them African-American spirituals, but that robs Tippett’s work of some of its sense of moment, and it is a piece that is, as the title reminds us, of its time. It seems to me that to use the language of the 1990’s to describe a work of the 1940’s is unfair to both the composer and the audience. And, to the extent that the word ‘Negro’ makes modern people uncomfortable, isn’t part of the purpose of engagement with a work like this to create discomfort? I would contend that sanitising art works of the past is a very slippery slope. Why should we let Wagner off the hook for his anti-Semitic tropes? I think it is highly questionable to attempt to clean up the record of a dead artist, to make them more acceptable to us than they would have been. There were, of course, real arguments over which Jewish artists could be claimed as Aryan. Both Mendelssohn and Mahler considered themselves both Christian and Jewish at times. What would it mean if history robbed them of either part of their identity, regardless of their motives?

Allow me to come back to Dr. King and his generation. Should we rewrite King’s speeches? Should we replace the word ‘negro’ in Malcom X’s “House negro and field negro’ parable? Should we change the title of William Grant Still’s ‘Afro-American’ Symphony to ‘African-American’ even though he was black? Surely the words of the dead belong to the dead. Be they black or white, Jewish or Aryan, gay or straight. It’s not for us, certainly not for me, to try to posthumously improve them or sanitise, update or improve their work for modern mores. I don’t think it’s right or helpful to put new and improved words in the mouths of people who are no longer with us.

Let the dead speak for themselves and their times.

A comment shared off-line earlier which I’ve decided to repost

I’m going to keep my head below the firing line on Twitter, but I appreciate you taking the time to comment.

Your comment “I think the problem that anti-appropriators consistently raise exception to, is the long history of musical creations by black artists being taken and reproduced by white artists and then making tons of money while the actual innovators remain poor and powerless.

Was one I particularly wanted to address.

This is what I’ve always called the Pat Boone effect, but it goes back further, of course. Every time there has been an emergence of a new kind of black music, there has quickly appeared a watered down, musically substandard white version. This is a purely cynical commercial byproduct of the entertainment industry and the racist nature of our society. It sucks and I think folks should call bullshit on it. I don’t think you can make any comparison to Tippett. But I thin you can make a comparison to hip hop, in which artists who by and large don’t sing, play, or compose sample the music of singers, players and composers and, with the help of huge corporate entities make a huge amount of money. Hip hop, with some notable exceptions, is basically a watered down, musically substandard version of funk for performers who can’t play and won’t study the basics of music. It just happens to be mostly black, but if all hip hop artists looked like Vanilla Ice or Eminem, I don’t think anyone would try to defend it as anything by a pretty cynical exercise. When I got to play with Clyde Stubblefield, he was (just barely) supporting himself as a cable TV installer while his beats were selling tens of millions of records all over the world. Surely that’s just as bad as Pat Boone. It’s been strange for me to see hip hop become elevated to a status where one almost can’t criticise it. When a black musician of the stature of Wynton Marsalis criticises it, he’s practically lynched. Including by a lot of well-meaning white liberals who don’t see why he can’t see that hip hop and jazz are really the same thing. Talk about ‘whitesplaining’! It’s worth re-reading what he’s said on the subject.

https://www.facebook.com/wyntonmarsalis/posts/10156215049577976?__xts__%5B0%5D=68.ARAq1K6GFkdktkoZWhaOLoBqFRFr4QoSQ-OnaU5S6TAz2v296e_Stfxmn8FdbLHzQ-Sfvqt7_45SB0XZoFTt6FBCzX38NVtPPfNsMIQqWA7BMkrvGDR2HdYbS2qSyl58D5LBK1MALhGhke8Ltn2ORNEaboQN1A9zfcBguYOEdYvwHPG_zGKtdsAX47O9M98psMW0uJMqcdRCDQZZrhmd4UIVNin7knTlS-OGwUF1koZdjrsqSQPFD98xbmy_51C03qR6Cl1xijYnRhT7sUPK-HhItiK6qC3WtQRprldZFimbH_s7BLzj7RZsvf6E6b18JxJMoDnlChVBaA&__tn__=-R

But not every example of a white musician getting rich and famous playing music with black roots is like this. Plenty of black musicians resented Dave Brubeck in the 1950’s and 60’s and criticised him and his band for not being in the same league as groups led by the likes of Miles or Sonny Rollins. I looked down my nose at his music for years. And fair enough, Brubeck and his quartet don’t begin to compare to their leading black peers on their terms as improvisers, instrumentalists, harmonic thinkers or composers. But, they did find their own path – it’s not hard bop, it’s not bebop, it’s their own thing and time seems to have rendered the judgement that it was a musical moment of real merit. Yes, it is probably unfair that he sold more LPs back then than Miles, but in the cosmic reckoning, history has recognised that Miles as the greater artist. And the fact that Brubeck kept playing the music for 40 years after his moment of fame passed tells you his interest in the music was an honest one.

As I said in my essay, musicians and artists can’t (or don’t) appropriate. Corporations do. Assholes do.

I personally disagree with the notion even that Porgy and Bess ought to be only sung by black singers. As a general rule, it’s right, but surely if a community opera company in South America or Indonesia or Siberia want to put on the piece and treat the material and the story with real respect, they should be able to without having to prove their racial purity.

Spirituals are a particularly tricky case study because nobody really knows who wrote them or how they came to have the importance they have. But, in general, music isn’t communally composed. It doesn’t belong to communities or races but to individual creators. I used to teach a course that went from Ragtime to hip hop and the mantra I gave my students then was that “the history of 20th C music is the history of American music, which is the history of black music.†I think in retrospect that it would have been better to say “black musicians.â€At the end of the day, it’s not the black community that opened the door to all jazz, rock and hip hop, it was Scott Joplin. Failing to acknowledge that he’s the fount of it all is just another kind of Pat Boone-ism. But, his biggest influence was Sousa. Joplin used /borrowed/’appropriated’ the Sousa march as his model for the rag. Does that take away from the blackness of the American musical project? Of course not, but it does show that music can only grow when ideas and styles can be freely used and developed by anyone with the talent and drive to put them to good use.

If we start giving ownership of music to groups based on color, you’re on the path that leads to the Mike Pence’s of the world saying “you can’t play that piece because it belongs to my community.†In fact, the Christian “rights†movement already does this. It says that “our right to maintain ownership of what we believe to be our cultural heritage and the space in which we think it should exists to be overrides everyone else’s right to participate equally in society.†I don’t see a material difference, only one of perspective, between that argument and the argument that says “this music belongs to my community and we get to decide who can play it.†Ultimately, I think there has to be a way of restoring social justice that isn’t based on further hardening of lines between people of different colors.

Anyway, I hope some of that makes sense.

Speak soon

Ken

Very interesting and helpful piece, Kenneth. It would, I think, be possible to agree with the main thrust of your arguments while introducing a defensible and significant distinction between appropriation as a (relatively) simple act of borrowing, and expropriation as a borrowing intended to demean, ridicule and subjugate, or as an act of economic exploitation. The confusing of appropriation and expropriation may be the place where controversy arises in unhelpful and confusing ways.

I do think looking at how music is appropriated, and how it may or may not amount to expropriation, in the social, political and cultural context of colonialism (etc.) is important. But I don’t think that goes against the grain of what you are saying here, and your comments on racism in relation to classical music are apposite.

I have slightly more difficulties with intrinsic value as simple assertion. Value is to do with demonstrable function, I think (technically, socially, politically etc.). I suspect that’s what you’re saying here, but it doesn’t quite come across that way to my (possibly ill-tuned) ears. So, for example, it’s simply a fact that ‘A Child of Our Time’ uses musical language which is more complex, developed and adaptable than that of ‘The Birdy Song’ – and that it generates passion, emotion and thought about issues of deep significance in the tortured realms of human history.

Hi Simon

Thanks for the comment.

Re- intrinsic value. There probably is a better word, but I haven’t found it yet.

When a piece is written, it is a finite collection of notes, ideas and possibly words and the ways in which those are developed within the piece. At the moment of the completion of the work, the work has within it all the possible interpretations and performances it will ever get. It carries in it all the potential to inspire or repulse, to uplift or sedate that it will ever have. All the qualities it will ever possess or could ever posses exist in the text at the time it is completed.

Bach’s music didn’t get better when Mendelssohn brought it back before the public. Other composers’ music may wax and wane in popularity or critical acclaim, but the actual piece doesn’t change. A good piece will always be a good piece, whatever we may say about it, and whether we enjoy it or not. The quality of a piece of art is absolute, it is our perception of it which is subjective. Likewise, a good or sympathetic performance might bring to the fore more of a work’s qualities, or win it more admirers, but it doesn’t add quality or or make it more admirable. Therefore, I would contend that the study of reception belongs within the study of sociology, not musicology, because reception (and performance history) have nothing to do with music.

Does that make sense?

Ken

Thanks, Ken. It makes perfect sense, though I’m afraid I’m struggling to agree! (As it happens I’m thinking a good deal about reception at the moment, in relation to my Tippett book and another music-related one I’ve written.)

A piece of music has intrinsic (though variable) *properties*, of course. But *value* is by definition an attribution of worth and a relational, perspectival matter. So I can’t see that it’s possible to claim absolute value or worth for something as an intrinsic property outside the realm of the theological. And I’m not using that word in the casually dismissive way, since I’m actually a theologian by academic training, and in significant aspects of my professional life. It might be possible to advance an argument for absolute value in music from the notion of absolute value in mathematics, though I don’t know enough about pure maths to do that — and I strongly suspect it would raise unassailable category problems.

I still want to argue for differential valuing and assignable distinctions of quality in music, however; but on the kind of grounds I’ve hinted at in my previous response, and which I’m developing elsewhere.

Anyway, it looks like we are on different pages on this one. But I still very much value what you have written… and it prompts me to go on mulling fruitfully, and contemplating the possibility that I am wrong.

Via email:

Dear Ken,

Thank you so much for taking the time to write this response, and I’m really appreciative that you were so thoughtful and probing of the issues at hand. I think sometimes music discourse skates over issues that are so relevant today because it’s easier to avoid difficult discussion, but for me these are exactly the kind of conversations we should be having and am grateful you were kind enough to offer your opinion. I can’t say I agree with everything you write, but am extremely grateful you took the time to write it. I’m really pleased that you decided to put it on your blog as well, and I hope to do the subject justice, as you did, in my essay.

Very best wishes,

A.S.

Via FB

If your cultural group has ever denigrated the music and art of another cultural community only to turn around and profit from its exploitation, it is appropriation. If you are truly inspired by it and include that culture in the context of celebrating its beauty and humanity, it is not.

I absolutely agree, although I’m uncomfortable with the idea of being part of a ‘cultural group,’ and especially uncomfortable with the idea that one could be assigned membership in a cultural group without one’s consent. It seems like a fundamental human right that one can decide who you are, who you associate with and what you believe.

Via FB: well-written, and, I think, true. You didn’t mention, which I would have in your place, that an author/composer has the right not to have the name s/he chose tampered with (I mean, in regard to the word ‘negro’ poss. being replaced by ‘African-American’ – which would have a completely different ‘flow’. ) I’m sure a composer thinks as long and hard about titles as any writer does. As you note, are we going to edit MLK’s speeches now? – unthinkable! A piece – even a piece for all time, like Tippett’s – is also a piece OF its time, as you say.

Via email:

Motivation is the issue, not the use of the material in itself. Surely MT was paying homage, showing solidarity and affection towards the black slave culture, as well as drawing a parallel with scapegoating at the heart of the Christian myth. The spiritual are also referencing Old Testament persecution of the Jews by Old Pharaoh.

The opening chorus of the oratorio makes the point that history is repeating itself – the cycles repeat and we should take heed about where such persecutions lead.

Tippett’s motives seem pretty benign to me, and the music is wonderful in context and performed as choral pieces. It would be a hard heart that would feel offended by such heartfelt, compassionate and sincere music.

If I dress, walk and talk like Ken Woods, I may be showing how much I admire him and want to be like him.

If I impersonate him to take his conducting jobs and steal his credit cards, then he would have every reason to be annoyed.

Quite a long thread on Twitter starting here:

Via FB

Excellent. I will be sharing this with my students. Gould’s Spirituals for Strings is up for next season.

Via FB

A very interesting read. Personally I find the Spirituals quite difficult (I’ve only conducted them as excerpted, not as part of the piece). I never feel more white, and more middle-class, than when conducting them; and always struggle with how the text should be pronounced (a minefield). I don’t feeling that immersing myself in the tradition would necessarily help, since Tippett has interposed himself in the middle. I’m not saying he did anything wrong, just that I find them problematic, and tend to avoid them when I can, beautiful as they are! But maybe that’s my own issue…

Via FB

Kudos on a thoughtful and well-written essay! While reading it, I remembered some quotes from Duke Ellington, early in his career, in which he expressed his dislike of the word “jazz” as a musical category, and stated that he thought of his music as “negro folk music.” So the word “negro,” as you observed, represents a period of time–back in the day, Duke was OK with it. (Although, later in his career, he appeared to warm to the word “jazz”–e.g. his great tune titled “The Feeling of Jazz.”)

One other thought: I think it’s dangerous to start referring to jazz musicians’ playing as “inauthentic” or “white” (even one’s own). IMO it would be more accurate to simply call it “not swinging” or “not happening.” Fact: Roy Eldridge, after stating in an interview that he could always identify a white musician on a recording, did a blindfold test for Downbeat, in which he was challenged to identify the races of the individual players in ethnically-mixed bands, and he got over half of them wrong. At jam sessions in NYC, I’ve heard musicians from all over the world run the gamut, from “killing” to “sad,” including some, yes, black musicians who IMO belonged in the latter category. If you hear, say, an alto player from, say, Japan, trying to play Kenny Garrett’s shit, and not really making it, does that Japanese musician sound “white?” Or does he just sound “sad?” I’ll go with the latter.

Cheers, Jon. Well said re “not happening” or “sad”. Exactly right. Good to hear from you. Many memories of our chats back in the day rose to the surface as I was writing this.

Via FB

Same for me reading it! I also appreciated your citation of Miles’ remarks about Bill and Gil. I’d add Lee Konitz, Keith Jarrett, Dave Holland, John Scofield, Mike Stern, Dave Liebman, Bob Berg—on and on. Miles hired cats because he liked what they played, regardless of ethnicity. Aside from just his music, Miles’ passing also deprived the jazz world of one of its all-time best judges of jazz talent.

Thanks for mentioning all these guys. I particularly thought about mentioning Liebman, Stern and Holland, but it would have been a detour from the main post.

Thanks especially for reminding me I haven’t listened to any of “Kenny Garrett’s shit” in way too long, and I am now rectifying that situation. What a force.

Via FB

I think Andrew points to the next thing – separately excerpted spirituals from Tippett, or, worse, by other white composers, for the feel-good use of white choirs. These are distinguished from the works of Dawson or Burleigh who were seeking to make the music accessible to non-black musicians. In contrast there’s a minstrelsy to the versions by white composers, a self-satisfied hokiness which I find very ugly.

I get this reaction from the suburban white choir singing African stuff. It makes me want to saw my own leg off when I see it. It’s so smug and disconnected, and it’s often tied to a sort of smug missionary mindset, which I also struggle with.

Via FB

I’m not entirely sure a mathematical expression such as a Venn Diagram is appropriate unless one can give a precise definition of art and of entertainment. What is art, within that circle, and what is not art and should be outside it? Also, the intersection of the two sets is, for me rather narrow. For me, Opera is art as well as entertainment. So is ballet, and rather a lot of orchestral music. Then taking lieder recitals. If they’re good, they’re entertainment. If I find them bad, then for me they’re not. Similarly for entertainment. All art that I like is, for me entertainment.

Via FB

I think we must always respect the ‘impulse to music’ that seems to be profoundly inherent in human beings whatever forms, simple or complex , it assumes–except maybe when music becomes purely intellectual construction…and even then…I once witnessed the profoundly musical members of a visiting Szczecin Choir from Poland able to join spontaneously in admirable singing of Afro-American spirituals by the Afro-American music students of the University of Michigan music school. Despite their very different places of origin they seemed to be coming from the very same place.

Via FB

You’re brave even to tackle the subject in the face of the two great blights on culture in our age: the universal assumption of bad faith, and the facile, first-week-in-sociology-class belief that the most negative meaning that can possibly be attached to a word, a text or a whole complex work of art is in some sense its true meaning. You’ve put it well, and you’re doing the right thing: the past is another country and we live in an age of xenophobes. Honest communication, in sincere good faith, is the only answer.

Thanks, Richard! The only really meaningful freedom in life is the freedom to decide who you want to be, what you want to do and who you want to associate with. Telling someone their identity is entirely based on your gender, race or nationality is the ultimate tyranny.

Via FB

Quite so: the all good/all bad world view denies autonomy, denies potential for change, denies agency and makes everything it touches narrower and less interesting. In the final analysis, it’s a lie that demeans us all.

Via email

I write you to express thanks for your weblog post of Mar 13, entitled _Tippett’s ‘Negro’ Spirituals_ (https://kennethwoods.net/blog1/2019/03/13/tippetts-negro-spirituals/).

In that post, you express an opinion I have had difficulty expressing to others, that Music, Art, Literature, etc., are the province of Humanity, not of particular groupings of people. I admire your defense of classical liberal values and the universal nature of music.

Indeed, there is just “good music, and the other kind”.

Via FB

I read this with mouth open, ready to argue with the first single misstep in answer. But I’ll be damned if he didn’t render my exact thoughts and feelings with much more eloquence than I ever could. This is wonderful.

Though I must say that even though I feel like he absolutely nailed the issue with the myth of appropriation in music, I’m sad that he didn’t go far enough to identify that cultural gentrification and some artistic laziness (cowardice?) *is* a problem.

I absolutely think Tippett (along with Dvorak, Delius, and a few others) absolutely nail it with the use of Black/Negro/Afro/Native American themes and styles, I hate that some of it (the Negro Spiritual “chorales” in particular) is taken out of context to avoid dealing with actual works of minority composers and musicians. The Tippett spiritual arrangements have become a safe way for many choirs to perform spirituals without approaching the themes of their inception or complicated feelings of white guilt.

This is brilliant. Thanks for sharing.

Via FB

Blown away by the briliantness of this essay. Keeping.

See also Mark Wigglesworth’s article in The Guardian”The piece is structured around the singing of five traditional Negro spirituals. On paper, placing them in the context of Tippett’s own contemporary language should not work. But it does, incredibly movingly, because at the very deepest level, our appreciation of these songs shows that we are all fundamentally equal. We share far more than separates us. The music reveals this connection, and to resist it is to deny the very essence of humanity. Tippett’s inspiration was realising that the spirituals convey a significance beyond their origin as 19th-century American slave songs, and that their music transcends time and place to poignantly unite the two extremes of the human condition: desolation and hope.”

Via FB

I liked the second part that was actually related to the question. The first part is a typical romanticized viewpoint about art. As if it is aesthetics that make something “authentic.†I can agree with him empathetically (I also sounded “white†on guitar), but not intellectually. Art is fundamentally human, but his statement falls along the lines of disembodying art. I know he isn’t doing that, and he certainly is well-informed, but his points are unrefined and poorly stated. Does any artist really have the right to perform any art? Do I have the right to call to the ancestors on a staged version of a Vodou ceremony as long as I have the right groove? He oversimplifies this and it undermines his arguments. He should have just answered the question directly rather than waxing romantic for more than a few paragraphs. (Sorry, musicologist coming out on FB)…..

Staged ceremonies. See Troupe Makandal (with whom I’ve performed). This is also art (people pay to see it), but it’s not musical tourism. The big problem here is he mentions musical whiteness as if it’s simply “not in the groove.†It’s so much more than this. Racializing music is such a complex topic (yes I realize he isn’t writing a dissertation), and he just glosses over it as if we all are on the same page. We aren’t, and that leads to your other point about the business. Music criticism is something that is fundamentally elitist. Not in a bad way, but that there is a arbiter of taste who speaks for the broader culture. That position is privileged. It represents a hierarchy that is neither arbitrary or easily codified. It’s fluid much like romantic thought. That somehow music (or any other art form) transcends humanity and becomes an “it.†Kind of like when Romantics use the term the “music itself†as if it stands on its own. That if we practice hard so we can “tap†into it we will be more artistic (or valued) than a neophyte or plebeian. This is how conductors and performers think (and what makes them so good), but it doesn’t work out intellectually. There are too many holes.

That being said, I like the part about contextualization of the title. One question though: am I allowed to say the full name of the song “Don’t call me n**%#r whitey†when I teach about Sly and the Family Stone.

Hi Brent

We haven’t met, but thanks for taking the time to read my blog post. I’m not aware of any time in my history that getting into a debate in a Facebook comment feed actually helped, but I do feel like there are quite a few aspects about what I’ve written you’ve either misunderstood or mis-represented.

You write: “The first part is a typical romanticized viewpoint about art. As if it is aesthetics that make something “authentic.â€

I don’t think there’s anything romanticized in what I said, but perhaps we differ on the meaning of the word. I fear you’ve completely missed my point about the intrinsic qualities of art being what it’s all about. If one accepts the definition of aesthetics as “1. A set of principles concerned with the nature and appreciation of beauty. 2 The branch of philosophy which deals with questions of beauty and artistic taste,’ then I think your description of aesthetics making something authentic is 100% the opposite of what I believe and what I’ve said above. People’s tastes change. People’s tastes are often wrong. People’s tastes are shaped in unhelpful ways, both positively and negatively. At the end of the day, I argue that the quality of a composition, a recording, a performance has nothing to do with the opinions, reactions or identity of the creator or the audience. Something is authentic if it’s authentic. Something is great if it’s great. Nobody gets to decide, and whether or not anyone or everyone gets a work of art, it doesn’t matter. Changing tastes don’t change the value of art. As JH rightly pointed out above, ‘authentic’ is probably an unhelpful word, but music is either happening or it ain’t, and people’s tastes, opinions or perceptive skills don’t matter.

I’ve also got to question where on earth you got this from: “he mentions musical whiteness as if it’s simply “not in the groove.— I think you need to read what I’ve written and not what you were hoping you could find to disagree with. Nowhere do I discuss whiteness in these terms or use the word ‘groove.’ If you look in the comments at the blog, JH has said it better than I said it in the essay, anyway: “I think it’s dangerous to start referring to jazz musicians’ playing as “inauthentic†or “white†(even one’s own). IMO it would be more accurate to simply call it “not swinging†or “not happening.†“ For a 19 year-old to thinkg “shit, I sound so white it hurts,†is a perfectly reasonable and accurate reaction, but as a rule, I think ascribing racial (or other identifying) qualities to any sort of failed performance is very dangerous and unhelpful. It’s only one step from that to “she plays like a girl.” See my comments about racist tropes about Asian musicians just as a starting point.

Finally, and I hope you’ll not take my tone as too argumentative or confrontational, I think you don’t really understand what music criticism is. Criticism is, or should be, about attempting to receive art (music in this case) with an unusually high level of perception and to explain to less experienced or knowledgeable listeners what you’ve heard. The role of a critic is not to vote thums up or thumbs down like Simon Cowell, or to tell us a performance or a piece is good or bad, but to contribute to wider understanding of music by articulating, as best they can, what they perceived a piece or a performance to be, or to be like. It’s an incredibly important role, and rather than being an elitist or hierarchical one, it requires real humility. The first job of a critic is to set aside what they already know and already believe and listen without prejudice. The best critic is the most open and honest audience member who has the knowledge and communication skills to articulate what they’ve perceived to others. Nobody’s perfect, but I think the standard of music criticism today in the UK (where I currently live) is actually incredibly high. Of course, there are critics whose own egos and agendas get in the way all the time, and some of them have very good jobs, but their failings shouldn’t cause us to misunderstand the paradigm of what a critic is or should be. It certainly shouldn’t be elitist. Good criticism can only be the outcome of complete humility and honesty.

There is a bit of elitism, or at least condescension, in your comments, I fear. I don’t think either critics or performers need a musicologist telling us our arguments ‘don’t work out intellectually†when your comments don’t make clear that you’ve understood them. And we don’t need you grading our papers. It’s my blog, and how many paragraphs I use is entirely my own business. My blog post was an answer to a student not a formal essay. I published it because I found that the informality and direct person-to-person exchange of ideas made it easier to express some concepts I feel passionately about than a more formal approach. For someone to sit back and say “I have insider knowledge which allows me to dismiss the work of this other person because I am a musicologist†is exactly the paradigm of criticism you rightly decry as “fundamentally elitist.†It’s just that, as I said in my blog post and above, this isn’t what real critics do. A real critic tries to engage with the most open mind possible and to understand the work they’re criticising as well as possible. With all the good will in the world, I can’t see that you’ve really done that here.

Which isn’t to say my blog isn’t wrong on several points, sloppy or overlong. It might be too long in some places and too short in others. I just don’t think you’ve made a well evidenced case that it is.

I hope we’re not getting off on the wrong foot socially here. Please take this all in the spirit of friendly and constructive debate.

Ken

Ken,

Let me try to respond the best I can based my limited time. Art has no intrinsic value. It’s value is based on human interactions. To say art has intrinsic value is to prescribe that it is beyond human. That is exactly what the romantics believe. I’m very aware of music criticism. I’m also aware that it flourished in the 19th century with Romantics like Robert Schumann (a very typical romantic I might add). So your view of music criticism is skewed by romantic ideals. I think there is value in music criticism as you understand it, but it should remain contextualized within the Western art-music tradion (regardless of which continent the composers/performers reside). But criticism of Carnatic or Hindusthani music isn’t the same as the music criticism you subscribe to even though both are art-musics. It seems you lack an understanding of Ethnomusicological principles. I can’t be sure of it, but your comments reflect it. Not all music is art. Music has been used to promote genocides. Negro spirituals May have become art, but they weren’t always performed for the sake of performing. They have a social and communal purpose. I’m not saying they can’t be treated as art, I’m saying it’s not the same as Porgy and Bess.

Regarding whiteness “My own love of jazz and blues music and my desire to transcend the whiteness of my own guitar playing taught me a lot. I can remember being in a jam session in my late teens and suddenly, painfully realising how incredibly inauthentic and white I sounded. My response was not to leave jazz and blues to black musicians, but to really study the music and the culture it came from much, much more deeply.â€

This was your original comment. Whiteness and jazz has an inherent hierarchy. I teach at the University of Miami, which is one of the best music schools in the world for jazz. However, we have very few African-American faculty. It’s a huge problem. The faculty and deans recognize it’s a problem. But our faculty also win Grammy awards, so it’s hard to fault them. Talking about playing white is very problematic. It probably shouldn’t be used (as you mention in your second comments relating it to gender – which by the way is also a huge problem in the jazz community at UM).

I will respond further when I have more time.

Hi Brent

Thanks for this, and I appreciate you writing when you’re pressed for time.

I’m glad we agree on the problematic use of the term “playing white.” I wish I had not used it above and will amend the text to reflect this. Of course, the reason it hangs around as an expression is that there is a history of some jazz played by some white players which embodies a different range of qualities and often hasn’t been, in some respects, worthy of the musics roots as developed by predominately black artists. If you put the names Paul Whiteman, Glenn Miller, Stan Kenton, Dave Brubeck, Maynard Ferguson Stan Getz and the Brecker Brothers on one side and Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis and Wayne Shorter on the other side, it seems pretty clear that the balance of excellence lies with one side, and the balance of financial success with the other. On the other hand, all those white musicians listed above made some great records. I think one has to judge their work on its own (often considerable) merits. It’s not fair to judge a Schubert symphony on the criteria you find in a Beethoven symphony. They were different artists with different aims.

I think we’re still not quite understanding each other on art’s intrinsic value so I’ll leave it for now.

Thanks again

Ken

As far as I can tell, you are basing your opinion about art’s intrinsic value on romanticized views about art’s “beautify and nature.†Philosophy about art is, well, Euro-centric and is valued in those contexts. Some philosophies of aesthetics are cross-cultural but some are not. I’m not very interested in aesthetic judgements about art. I have my informed opinions and they are both, as you mentioned previously, fully valid and invalid. They are subjective and “tastes change.†Many cultures don’t value aesthetics like the Greeks did, and that is OK. Confucius believed music would order society. He’s both right and wrong. It’s a philosophy. They are like theologies, numerous and often contractidtory. The only intrisic value art has is that most humans agree that it’s good to do something creative outside the basic functions of daily life. But this requires time, resources, and specialists. Not all cultures have that luxury, but they are neither good or bad. Maybe they don’t have an abundance of technology, but they still spend hours of the day making “art.†Once again, I’m not interested in western philosophies about aesthetics. I’m interested in people making music. And I’m the many cultures I’ve studied, aesthetics are only a portion of what people value. I’m an ethnomusicologist and thus interested more in the human interactions surrounding music than I am with aesthetics. And that is what your analysis is missing. Art is not primarily a product of philosophy it’s a product of human relationships. When you understand art from that perspective, aesthetics, while important, are not at the center of music making. If you base value judgements on aesthetics, you miss the most important aspect of music making.

This leads me to your point about art being for anyone. Yes, as long as aesthetics is the primary value of that performance practice. I would say aesthetics are not fundamental values of negro spirituals. They can and have become art, and I think they can be performed as such. But there is something very disconcerting about the “world is my oyster†philosophy. It’s very imperialistic and overshadows important aspects of human relations such as indenity politics and economics. An example of this is Paul Simon’s Graceland. It’s a great album but very problematic from a socio-cultural perspective. Also from a general ethical perspective. It deserves all of the criticism it got. I would say enticing musicians to cross picket lines where their friends are being killed by paying 3x scale for musicians is questionable ethically, especially when the product didn’t really do much to end apartheid other than to foster counter arguments about its lack of attention to apartheid. This is where aesthetics cannot be the driving force behind music making.

I hope this makes sense. Forgive any typos as I’m doing this on my phone.

Hi Brent

Very interesting stuff. Thank you

I’ll make one more stab at this whole ‘intrinsic thing.’

A piece of music will intrinsic and extrinsic qualities. The intrinsic qualities are those concrete aspects of the piece that, all things considered, are as permanent and specific and finite as those things can be- the notes, the rhythms, the text, the relationships between the notes, etc. The extrinsic qualities might include anything from received wisdom about the piece, titles, programs, etc. A piece like Mahler 3 can shed it’s program at the composer’s whim. We can find out generations late that Schumann specifically didn’t want a title for his E-flat Major symphony – it was the publishers who called it Rhenish. Extrinsic aspects also include all kinds of history of reception, performance practice, critical response, biographical context etc.

All of those qualities can change at any time. At one point, Mahler and Mendelssohn’s music was banned in much of Central Europe because, like all Jewish music, it was viewed by the Nazi’s as Degenerate. However, no amount of racially driven criticism could ultimately change the fact that most of that music, from Mendelssohn to Klein, is really fantastic. Narratives around music and opinions around music change, but the music doesn’t change. I don’t think its romantic or airy-fairy. I think it’s about as scientific as you can get about music. A piece of music is a finite gathering of material, in which is implied a huge range of relationships and possibilities. Nothing that performer does or an audience member experiences or a critic says changes that. And to the extent that any piece of art can have any value, I think its value comes from the intrinsic qualities of the work.

And I would say this applies equally to other musics. Jazz is, after all, spontaneous composition. Although it is an interesting philosophical question as to at what level a tune is a composition in jazz.

Not sure I agree re Graceland. Whether the hiring practices were ethical or not, I am not well-informed enough to say, but I think that as soon as you say to anyone ‘you can’t play this music because you come from another part of the world,” you’re opening things up to those who would stop Asian violinists playing Bach or William Grant Still from claiming the symphony, handed down from Haydn to Beethoven to Bruckner, as his own. This isn’t theoretical – it has happened historically. It’s the same reason Joplin’s life was kind of ruined by Treemonisha – people thought opera belonged to German cats.

Do you know Zappa’s credo? Anything Anytime Anyplace For No Reason At All.

I might change the last bit to “Anyplace by Anyone”.

Many thanks again

Ken

Ken,

Sadly, we are never going to agree. I’m very aware of your understanding of the “intrinsic value of art,†but you seem to be restating your opinion about it while fundamentally being unaware how much you are influenced by romanticism. You seem to hold on to this universalist view about music that just doesn’t exist in reality. Even the terms you used to describe music are exactly what ethnomusicologist have been picking apart for decades. There is no difference between intrinsic or extrinsic aspects to the music. They are one in the sand. You should really look into Christopher smalls concept of music an for decades. There is no difference between intrinsic or extrinsic aspects to the music. They are one in the same. You should really look into Christopher Small’s concept of musicking. Or just read a world music textbook for undergrads. It might change your lens. At least that would be a good start for you.

Good luck!

Hi Brent

Happy to agree to disagree and grateful for all the constructive discussion. I don’t need another world music textbook, I promise. I think what I think and say what I say not because I don’t understand the concepts you’re putting forward, but because I do. But I can see you feel the same way, and that’s fine. I hope you’ll re-think the intrinsic/extrinsic thing over time.

Warm best wishes

Ken

Thanks Ken,

Thought provoking indeed. As far as the intrinsic/extrinsic issue, I will only classify music in categories (i.e. aesthetics, activities, ideas, and material culture). The only time I use a binary division is sonic vs concept, but they are music one in the same. The big problem with using your terms is that music is essentially an object. It’s pretty much everything I’ve argued against most of my professional career. Music is foremost a verb and should be thought of as such. Music as a noun misrepresents how fluid the meaning is and all of the components that go into it. It’s not like visual or literary arts. It’s more like theater with actors, staging, makeup, literature, philosophy, etc., but even more fluid. Too many working parts to cosider it a noun. It’s really hard to argue against that. Most musicologists and ethnomusicologists agree on this point.

Is the value of art/music limited only to its own context of history and culture, i.e. no more than a cultural construct which only has relative meaning and relevance. If this were true, then it would make the study of the music of other cultures pointless, since we would have to admit to no possibility of ever understanding them. We might as well let others get on with their cultures without judging them or assuming any rights of access. But cultural exchange and diversity lead to enrichment, if the dialogue is motivated by respect and a desire for deep understanding. Takemitsu is a good example of a composer who fused Eastern and Western elements in his music, influenced greatly by Debussy – who had done something similar fifty years before. This profound dialogue across time, space and culture brought us much beautiful music and enhanced cultural understanding, despite all the terrible things that have also happened between Europe and Asia across that same period.

Great art transcends cultures, contexts, history etc, because it taps into archetypal values such as compassion, longing for transcendence, love and harmonious being. We can also share feelings of rage, jealousy and hatred with our fellow human beings, which are also part of the common patchwork of human experience. Human nature at a deep level is shared by all, and great art originates at this deep level as the play of instinct and archetype. Good music should grow out of the tension that exists between our desire for harmony and our ability to make the patterns that lead us to that goal. At the level of feeling, these are simply patterns of energy which can be as simple as binary code. Yes-No, On-Off, Zero-One, sound-silence.

You can play with these patterns in myriad different ways and manifest them in myriad different styles and complex forms, but the fundamentals remain the same. Any outsider engaging with such works of art might require a process of learning and assimilation, but that doesn’t mean that it cannot be done. This then justifies the study of music from other cultures and from other periods of musical history because, while we cannot be sure we are hearing things with the cultural ears of a particular time and place, we can perceive eventually those archetypal layers, which allows us to in some modest way to appreciate and absorb them.

If we emphasise cultural difference by concentrating on differences of style and convention, we give weight to the irreconcilable differences, which leads to culture wars and false accusations of misappropriation. Put another way. If I meet a being from another planet with two heads and three arms, I can react by dismissing him/her as an ugly deviant to be condemned, or I can see that like him/her I have a head and arms, and that might be the best way basis for dialogue – what I share, not what is different.

Tippett saw a linkage between cultures, moved by his deep compassion for all humanity’s suffering. That he expressed himself through the medium of Western art music does not invalidate his synthesis, but makes it possible, because Western Art is uniquely open to outside influence. Tippet expressed himself eloquently in his own culture by reaching out to other cultures. It is a critique of several millennia of slavery, oppression and discrimination – the Egyptians enslaved the Jews, the white man enslaved his black cousins, the Nazis turned on the Jews and other minorities. It is a universal flaw of human kind to behave in this way, and a creative vision transforms the specific into the universal. holding up a mirror not just to Western man, but all humanity. We can and must recognise universal values in our culture and other cultures, and of course, why would we not be more at home in our own culture? It belongs to us, but we can still generously give it to anyone open to receiving it, and without imperialistic intent or a sense of superiority.