A question from a friend prompted a quip which amused us both enough that we thought I should share it on Facebook:

Q: “So Ken, what are you going to do if everything gets shut down [for coronavirus]?”

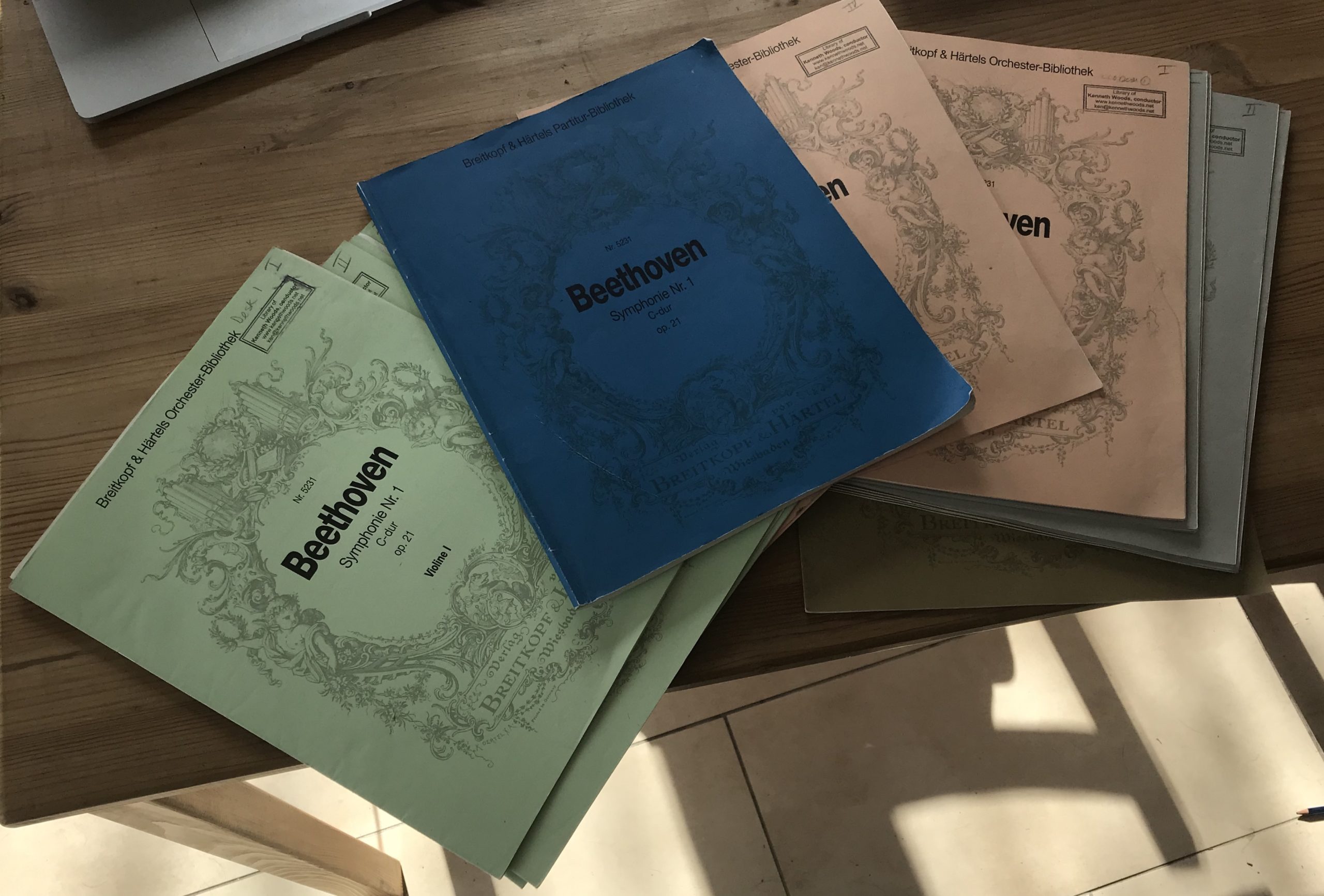

A: “Study [scores] like a m*therf@cker, and try to write a symphony.”

As I was getting ready to post it, however, I thought people reading it might be a bit baffled. After all, I conduct all the time. Doesn’t this imply I’m studying all the time? Is this an admission I’ve been winging it?

In fact, it occurred to me at that moment that it might be a nice idea to write about how I see the difference between “score study” and “score preparation.” I think there is something to be said for conductors (and other musicians) looking at these as two largely separate, but equally important, elements of your musical well-being. It’s a good idea for all of us on the podium to take stock and make sure we’re giving adequate attention to both endeavors.

For purposes of this post, let me explain my idea of score study work that is aimed developing one’s understanding of and sympathy for a piece of music. It’s what you might call “holistic” learning. This might include any of the following:

- A motivic analysis of the work

- An in-depth examination of a particular section, or even passage in a piece

- Research into the work’s genesis and reception

- Reading works of analysis

- Studying the biography of the composer

- Studying what music, or other stimuli, might have influenced the composer while writing

- The influence of folk music or other vernacular music on the piece

- Studying performance practice, original instruments, etc

- Listening to recordings

- Learning about musical quotations

- If there are literary texts involved, learning about the poetry, developing your understand of the language, etc

This kind of work can unfold in all kinds of ways. It need not be applied to an upcoming performance. Importantly, in and of itself, it may not in any help you to perform a work well in and of itself. If it did, musicologists and theorists would make the best conductors, and, well….. er…… Enough said!

Score study can also be piecemeal. One might wander into a score after hearing the piece in a concert and spend a few hours thinking about a single aspect of the work. One might do a ferociously intense analysis of one movement of a symphony without learning the whole piece. No harm in that. It’s all grist for the mill.

Another interesting facet of score study is that, just as it need not be tied to an upcoming performance, it generally has a long expiry date. I can still get out a score that I learned in the 1990’s and be pleasantly surprised at what my younger self learned from it. One always re-thinks things (if one is paying attention to life), but the study we do today will be with us for the whole of our journey with the pieces we perform.

Score preparation is a far more specific and goal-oriented process. It is much closer to instrumental practice than score study, which can be divorced completely from applied music. It might include any of the following

- Singing through the piece in character and in time (either silently or out loud)

- Working out beating strategies, thinking about gesture, practicing gesture

- Conducting in silence

- Working with metronomes

- Playing things at the piano

- Working on memorization

- Figuring out who to cue, when and how

- Working on the reliability of your tempi

- If there is a literary text, practicing speaking/singing it. Working on pronunciation

- Practicing singing/conducting organic ritardandi and accelerandi

Every conductor is different, but for me, I find it hard to study once I’ve started to prepare, although preparation usually brings several further moments of insight because you get so deeply involved in the material. Preparation, for me, marks a huge narrowing of focus. Looking at recent ‘big’ pieces I’ve either learned, like Die Walküre and Mahler 10, or re-learned, like Ein Heldenleben or Mahler 1, I can study a piece for many, many months, but tend to feel happiest narrowing the focus to preparation 2-3 weeks before a concert. Often less if I know the piece well or if it’s not too long or complex. Of course, concerts don’t happen in a vacuum, and one reason I prepare pretty close to the concert date is that there are other pieces on the schedule in the weeks before. Finally, as a matter of professional survival, I have a method for preparing a score overnight which has saved me more than once.

Preparation can be entirely practical and pragmatic. As an example, it is entirely possible (although not advisable) to prepare an entire 12-tone work without ever once giving any thought to what the row is or how it is used.

Let’s face it, we’ve all played under conductors whose score preparation was lacking. We know the symptoms. Head buried in the score, arms flailing, tempos changing every time he/she turns a page, not knowing what’s on the next page of the score… It’s deeply frustrating for the musicians and often terrible for the audience. And, be honest, at one point or another in life, we’ve all had to wing it and pray.

Just like a player has to be able to play the notes, a conductor needs to be able to attend to the nitty-gritty of your job. And, unlike score study, score preparation needs to be refreshed. Of course, re-preparing a familiar work is always a faster process than learning a piece from scratch, but every conductor at some point has made the mistake of thinking “that will be fine, I know it well,” only to be caught out. Remember, your soloist has probably played their Bruch Violin Concerto or Grieg Piano Concerto a hundred times, but they still have to practice it or it will be sloppy. The same goes for us.

So – does this mean that once you’ve studied a piece, you can get through future performances just on the basis of preparation?

I think you already know my answer.

It’s not that you can’t pull an old friend like Tchaikovsky 6 or Brahms 1 off the shelf and just review it and do it. You can. In fact, you will have to many times in your career.

It’s that too much of that kind of work eventually alienates you from the joy of discovery and the love of music which set you on the path of conducting in the first place. There’s nothing for a conductor like the thrill of developing a new understanding of the musical mind of one of the greats. We live not only for making music onstage with wonderful colleagues, but for those precious moments of private revelation. And a lack of curiosity and renewal will definitely make your conducting a lot less interesting to your colleagues, no matter how proficient your technique and preparation are.

Every conductor I know has more demands on his/her time now than in previous generations. Our non-musical duties seem to expand with every season. Email is a curse, but the phone is a prison. Our orchestras and festivals seem to need our attention year-round and around the clock, it often seems. Many of us teach, and family also needs time and energy. Managing our time is an endless exercise in something like triage – what do I absolutely have to do? As per my quip (“study scores like a m*therf&cker”), I often feel like between performances, administrative responsibilities, family and travel, genuine time for quiet contemplation often feels hard to find.

Fortunately, as I said above, score study is a very flexible process. Rather than driving yourself mad with guilt and frustration that you don’t have the time and head space to re-study every work you’re conducting this year the way you did when you were in your 20’s (and trust me, aspiring young conductors, if you become a working conductor, this is the least busy you will ever be, no matter how busy you think you are now), give yourself permission to graze. Nibble on a bit of Bartók’s approach to rhythm, or spend a few minutes looking at a Haydn minuet with a glass of wine instead of reading the paper or scrolling Facebook. It might just help you bring that kiddie concert on Tuesday to life with a bit more spirit.

Or… it just might make you feel a bit happier about life.

Recent Comments