Feature Article by Colin Clarke

A fair amount of the music of Steven R. Gerber has been covered in the Fanfare Archive, including the First Symphony and Viola Concerto (Chandos, Fanfare 24:2), and a possibly difficult to find Koch disc from over 20 years ago featuring the Violin Concerto, the Cello Concerto, and the Serenade for String Orchestra (Fanfare 24:3). But, on hearing the present Nimbus disc, Gerber’s music seems under-represented, given the fine craftsmanship on offer. One hopes this interview may go some way to rectifying this situation, and invite in further explorations. This interview features the conductor of the most recent Gerber disc on Nimbus, Kenneth Woods, and the arranger of three of the pieces, Adrian Williams. (A second arranger, Daron Hagen, was not interviewed.)

Would either of you like to give a brief introduction to Steven R. Gerber (1948–2015) and his music? I know he was born in Washington, DC, and studied with Babbitt, Earl Kim, and J. K. Randall. Certainly, the implication of this is that the music might well be hard-hittingly atonal, but what we hear on this disc is far from that. I believe a new phase for him started in the 1980s and grew into a new sense of tonality?

KW: Yes, that’s correct. Like many composers of his generation, he grew up with a firm grounding in mid-century Modernist techniques, but gradually moved towards a more tonal, flexible language and more traditional forms. His mature works show him focusing his creative energies on genres like the string quartet, the concerto, and the symphony. And while some of these works can be quite spiky, his use of dissonance is more akin to the language of Bartók, with its rich variety of light and shade, than the unrelenting dissonance of much post-World War II serial music.

The Sinfonietta No. 1 is an arrangement of the 1991 Piano Quintet—and the arranger is Daron Hagen. This was a commission by the Gerber Trust, I believe. There’s no missing the Stravinskian quality to the wind writing in the first movement (and those sharp string punctuating chords!). There seems to be a real wit here, too. Kenneth, you mention the similarities of the First Sinfonietta’s Mesto finale to Bartók’s Sixth String Quartet—would you care to elaborate on that for our readers?

KW: Yes, I think there is likely a bit of a sense of homage in this work. Remember, this work was originally a piano quintet, and that sense of dialogue with the past has always been an important part of that genre. Bartók’s own First Quartet opens with his own homage to late Beethoven. To be clear, Gerber isn’t quoting Bartók; rather, he is evoking an atmosphere, one of great stillness and sadness, that is pretty easy to spot if you know the older work. It’s the same with Bartók’s First—the notes and motives are all his, but the atmosphere is very much Beethoven’s.

Adrian, you’ve arranged Gerber’s Fourth Quartet as String Sinfonia No. 1. This is a very different score—more rounded, although still with some nicely scrunchy harmonies. What drew you to this piece for arrangement? This is a somewhat softer-edged piece, decidedly mysterious in places.

AW: Yes indeed. First, I must say that three quartets were chosen for arrangement; two would be for strings only, and one would get the royal treatment of full symphony orchestra. It is illuminating to place this new arrangement alongside the others—in particular, either of the new Sinfoniettas—and be aware of its relative softness. The occasional scrunch comes, as is normal with almost any Gerber. So, I saw arranging this piece as part of a varied package.

Adrian, you use the double bass selectively, I believe, in this piece. Certainly, much of the piece sounds quite luminous (particularly the Lento second movement). Can you talk a bit about how you (and Gerber) use texture?

AW: Evidently, from the fact I chose Quartet No. 5 to be my full orchestral arrangement, I did not see No. 4 as having that level of orchestral potential. However, it does have that luminous quality you mention, which is well if not best served by being arranged for strings. I felt it was not necessary, or even desirable, to use the double bass much, but I feel it gives textural variety and depth when needed. This piece works well with full strings, maybe even better than as a quartet—but I shouldn’t speculate on that!

It was this second movement of the String Sinfonietta that really brought home to me that Gerber never wastes a note—everything has a point. How did that sense of concision affect the way you approached the score?

AW: The String Sinfonia No. 1 has a very varied demeanor. For example, there is the intensity of the third movement Maestoso con moto, with insistent rhythms and dense harmonies, against the stripped-down magnificence of the Lento, and the sense of a specifically American territory for the final “Postlude.”

Would either (or both) like to explain the concept of tempo intensification, and how Gerber realizes it in both the First and Second String Sinfoneittas?

KW: Well, he’s very systematic in marking ever-increasing metronome markings. The gradations are pretty small, which means I have to be very secure in remembering a good 20 tempi per movement—that is a fun challenge, especially in a recording. But the overall effect is fantastic—by the time the listener realizes it’s getting faster, the knots have already tightened.

The Two Lyric Pieces for strings are not arrangements, but originals—the second in particular is really powerful, a passacaglia that seems to grow out of the first one. I love this piece, with its sense of slow unfolding and how Gerber creates that registral separation between the stratospheric violin and the slowly, inevitably moving bassline. This came a bit later as a piece, in 2005, and I’m wondering if you’d agree that the sense of every note counting is even more marked here? The sustained harmonies in the Introduction, for example, against which the violin sings, seem perfectly judged in terms of the dissonance-level.

KW: I think sometimes listeners underestimate what it takes to write a great miniature. Gerber says so much in each of these pieces—they really explore their respective universes. I think in his later work, you start to hear more “American” elements—certainly, that evocative opening is something only an American composer would probably write. But then, there’s that suave Berceuse! Wonderful.

Would either of you like to introduce the excellent soloist to readers, Emily Davis? She’s associate leader of the RSNO, I believe? She has a fabulous sound, and seems to have such an intuitive understanding of Gerber’s piece.

KW: I was introduced to Emily’s playing by my colleague, the ESO’s wonderful assistant conductor, Michael Karcher-Young. Incidentally, Michael played an invaluable role in proofreading all the materials for these new arrangements. We couldn’t have made this disc without his help. Michael sent me a message along the lines of “You’ve got to hear this violinist,” and I was suitably impressed with what I heard. Later on, she came in as a guest with my wife’s orchestra, the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, and Suzanne (my wife) told me that Emily was as nice as she was talented. She’s been a regular guest leader of the English Symphony Orchestra over the last two years, and we always love to have her back—she’s not just a fabulous player, she helps galvanize and inspire everyone around her.

The String Sinfonietta No. 2 is an arrangement of the String Quartet No. 6 (2011), one of Gerber’s last works. Can you tell us a little bit about the techniques of tempo intensification here? We saw that in the first String Sinfonietta—is this a Gerber formal characteristic?

AW: I’m not sure about formal, but this characteristic does rather point Gerber out! It’s one that I appreciate and enjoy employing in my own works from time to time. As Ken says, the listener may not notice the “accelerando” is happening as the increments are so tiny—and challenging for the conductor to expedite! The astute amongst us may notice after quite a number of cranks up in tempo!

Kenneth, what challenges does that technique of tempo intensification bring up in performance?

KW: I think that whether one approaches it as a conducted sinfonietta or as a string quartet, the interpreter(s) really have to have internalized the tempi. Speeding up with an orchestra is kind of risky at the best of times—it’s so easy for things to sound like they’re either rushing or lurching, rather than very gradually intensifying. But there’s nothing more exciting for a conductor than when it works and you can feel everyone willing the music forward together.

Most imposing of the movements of the String Sinfonietta No. 2 is—to me at least—the finale, the Theme and Variations. Gerber seems to have been really at home writing in this form—his music seems to hold a real sense of ferocious curiosity about his own materials, and yet he allows the variations (or, for that matter, the Passacaglia) to unfold slowly and inevitably. Adrian, what were the challenges in expanding those variations to fuller string forces?

AW: I did not find this so challenging, to be honest, as there is no point in trying to elaborate further something that is already very fine. In the same way it can be said that some poetry is ruined by unnecessarily setting it to music. But in this case it was good to be mindful of how the texture would change, and be aware that parts which give prominence, say, to the first violin, would still be better with a solo violin rather than the whole section. It’s not obligatory to use all of the string orchestra all of the time. Hence the matter of the occasional use of the double bass.

We move to the year 2000 for the String Quartet No. 5, here arranged as the Sinfonietta No. 2. I’m not sure I would have guessed this was an arrangement, so idiomatic is the orchestration. Adrian, did you extend the orchestra here to include woodwind and brass in order to reflect the punch that the material holds?

After considering for some time which of the quartets should be awarded the prize of full band, I realized No. 5 had the greatest potential for orchestral color, especially the Theme and Variations (the second movement/finale). As a quartet I found the continual dissonance (inherent in the theme) through the variations quite tiring on the ears, but very inspiring to imagine orchestrally. Despite those dissonances, each variation has its own characteristic, so the idiom allows each to slide neatly into the next. It is a stroke of genius that allowed Gerber to superimpose the main themes of each movement over each other in the closing bars of the work. With a little tweaking this works wonderfully and brings it into a glorious more tonal light.

Adrian, you’re a composer yourself. Would you say that acts as a help or a hindrance when arranging other peoples’ scores (and why)?

AW: I’m not totally sure. I don’t think it’s a hinderance, certainly. As for help, I don’t think it can be. When arranging, I simply allow my imagination free reign. It’s something I absolutely enjoy and find fulfilling. Maybe this is a good moment to mention Ken’s own fabulous orchestral arrangements of great classic chamber works, since modesty forbids him to mention them himself: the Brahms Piano Quintet in A Major, Tchaikovsky String Quartet in E♭ Minor, et cetera, ad infinitum.

As a composer, Gerber seems to have been active in a wide variety of idioms—there’s the symphonic music, but also the piano music (Albany). What further plans do you have for the future?

KW: Next year, we will record Gerber’s Second Symphony, and I’m very excited about that as well.

All of the works on this disc appear in world premiere recordings. Adrian, are there further arrangements tucked away in a drawer waiting for the light of day?

AW: None in a drawer or anywhere! However, if I am approached about arranging other works, I will look at them with great pleasure, as it has been a huge privilege to have been commissioned to make three of the arrangements on this disc.

Finally, I feel I should acknowledge the fine recording (Wyastone Concert Hall—Phil Rowlands, producer, and Tim Burton, engineer). What sort of mike placements did you use? Long takes or short? It’s wonderful how the recording captures clarity but also warmth—and the combination for the two is difficult to achieve!

KW: Phil Rowlands was our producer for this disc, and he is a real wizard of sound. Recording under socially distanced conditions makes everything more difficult for the musicians and the producer, but he’s done a masterful job of carefully blending some closer mikes with the main stereo pair for the mixture of bloom and clarity you’ve noticed. As far as the management of the sessions, it varies enormously. There’s a myth that long takes are always better, but you can often hear the musicians run out of gas after a few minutes, so it’s important to let your ears guide you rather than any pre-conceived concept of what will get the best result.

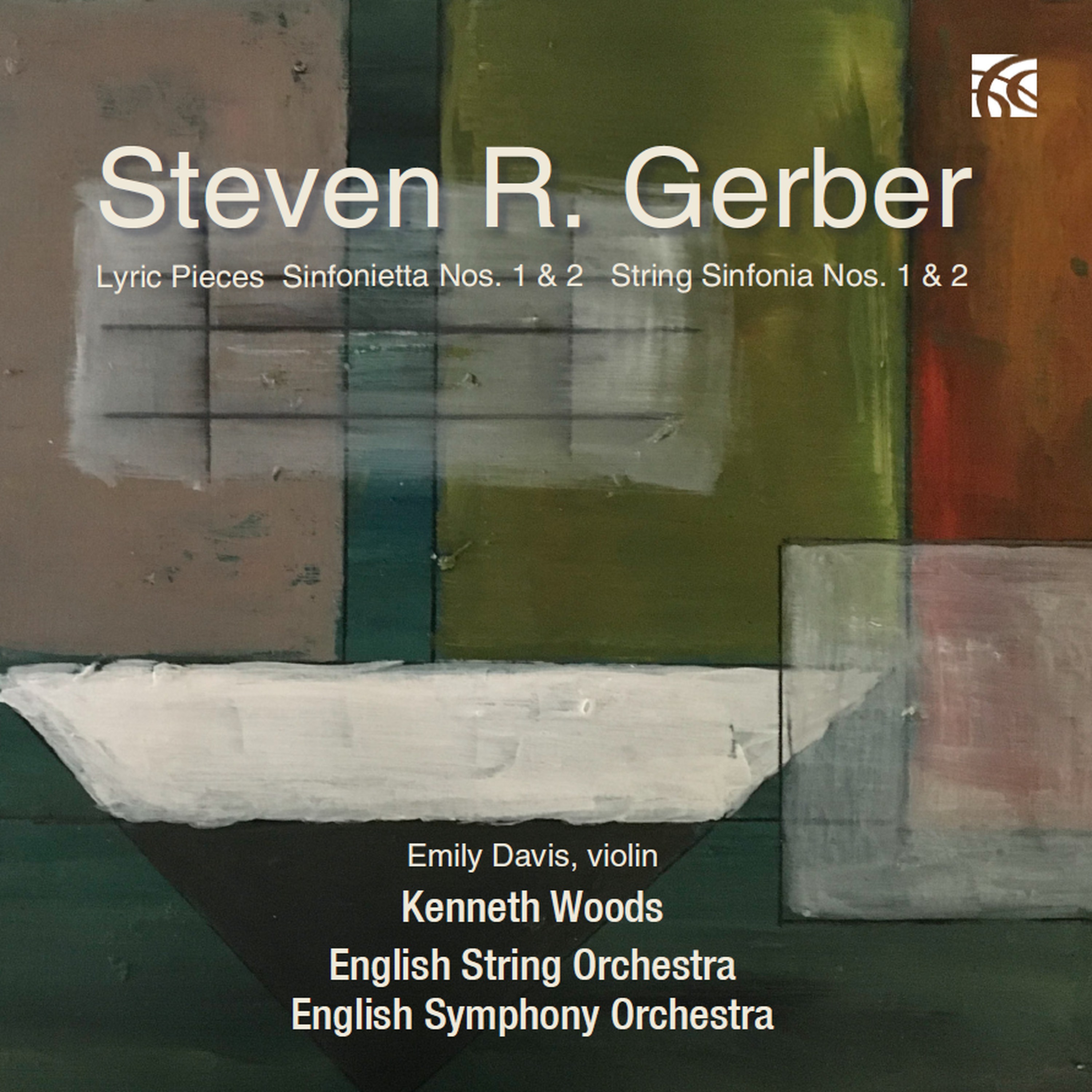

STEVEN GERBER Sinfoniettas:1 No. 1 (arr. Hagen); No. 2 (arr. Williams). String Sinfonias2 Nos. 1 and 2 (both arr. Williams). Two Lyric PIeces3 • Kenneth Woods, cond; 3Emily Davis (vn); 1English SO; 2, 3English Str O • NIMBUS 6423 (73:07)

Recent Comments